Mary Watt, chair of UF's Department of Languages, Literatures and Cultures, explains why medieval studies may be more relevant than ever.

I am neither an engineer nor a physicist. If I were I would probably spend much of my time trying to build a time machine so I could go back to the past and find out what it was really like to be in Rome when marauding Visigoths sacked the city in 410, to feel the mixture of joy and guilt at surviving the Black Death that devastated Europe in 1348 or to understand what inspired Columbus and Vespucci to take to the open seas guided only by a signal in the heavens.

In truth it was my impatience (apparently time travel is taking a lot longer to develop than it does in the movies) and my insatiable desire to experience the past, to engage in conversation with my cultural ancestors that led me inexorably to medieval studies and to Italian medieval literature in particular.

As a child I had been fascinated with cultural transformation. I knew about Romans and I knew about Italians, but I wondered how the former had become the latter and equally intriguing to me was how Latin had become Italian, and Spanish and French for that matter. Had the world changed that much in two thousand years? Had the people? In some respects it seemed that the people of Pompeii shared pretty much the same worries and enjoyed the same things we do today. The mosaic sign “cave canem” (beware of the dog) discovered under the ashes of Vesuvius, suggested on one hand that those people were not all that different from my own neighbors. On the other hand, regular inoculations and visits to the doctor were a normal part of my childhood and dying from bubonic plague or leprosy was unthinkable. I wondered what it must have been like to live in times where the possibility of sudden death through violence, starvation or disease was immediate and ever present. I began to wonder how living “in the valley of the shadow of death” affected the way people felt about their own lives, whether it made them hopeless or spurred them to live life to the fullest, carpe diem and all that.

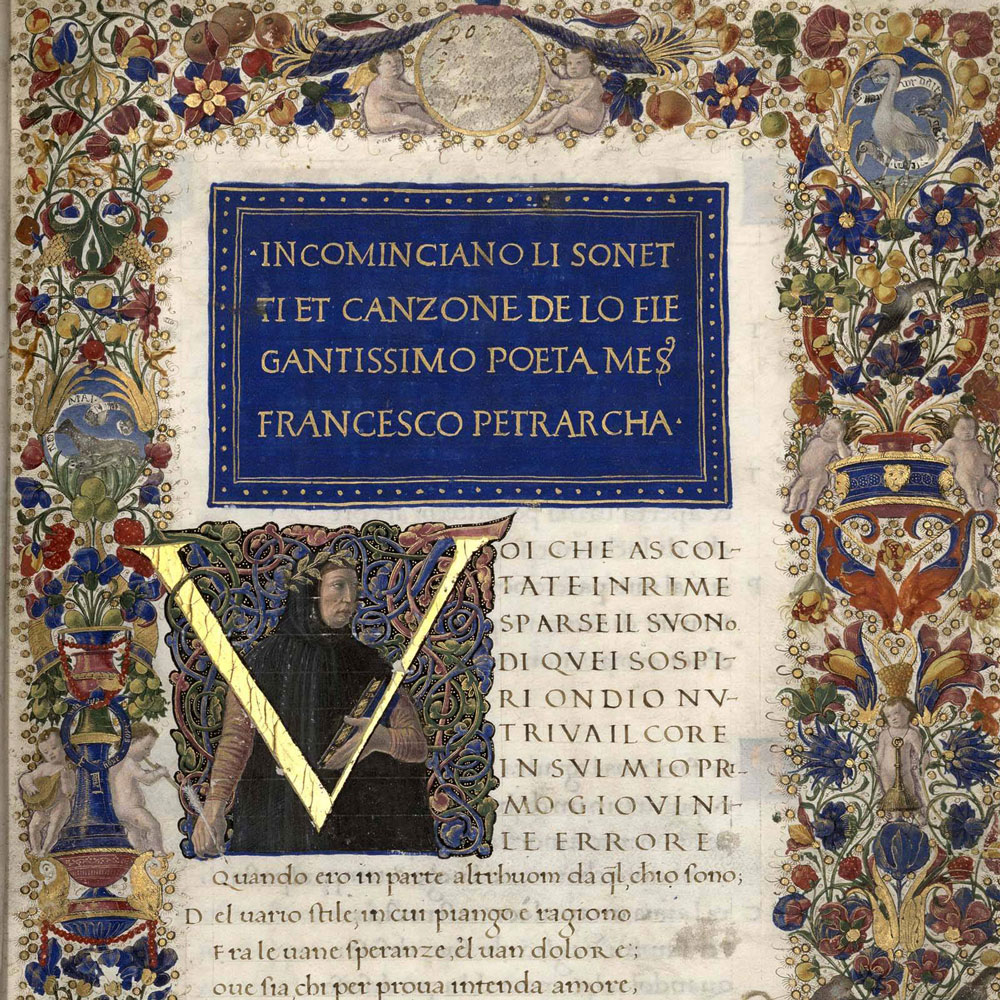

Francesco Petrarca’s "Canzoniere" allowed me some insight into such questions. The work consists of 366 poems and is dedicated to his beloved muse, Laura, who died far too young. Petrarch’s poems describe the searing sweetness of unrequited love, the anger he feels at Laura’s death, his desire to die just to be with her while at the same expressing his hunger for fame and his desire to live forever. St. Augustine's "City of God" describes the shock and despair of the Romans who thought their lives were secure and their city impregnable until Alaric and his hordes breached its walls and ran amok in the streets, raping and pillaging for days on end. Augustine recounts their terror and suffering as he tries to console the survivors and provide an explanation for the incomprehensible. In his "Decameron," Giovanni Boccaccio chronicles the response of the Florentines to the Black Death that stalked fourteenth century Europe, encapsulating the horror of the plague in his chilling description of a woman sewing her funeral shroud from the inside out because there was no one left to bury her.

These are real voices that still speak loudly above the noise and constant technological stimulation that surrounds us. They make us wonder if, despite all the technological and political changes the world has seen, humans have remained unchanged? Or have the many advances in technology transformed us as well? Does the probability of a long life affect how we value life, our own lives and those of others? Do the extra twenty or thirty years we imagine we have cause us to put off our lives’ great ambitions or motivate us to do more? And if so more of what?

Moreover, reading the notebooks of Da Vinci, the dialogues of Galileo or the consolations of Boethius, allows us also to see how humans many centuries ago imagined the world could be and gives us a sense of why our world is the way it is. I have recently been reading an unfinished book by Christopher Columbus in which he lists all of the many prophesies he believed he was fulfilling by sailing west to reach the east. It makes me ask myself if he would have made his daring journey had he not been aware of these prophesies. At the same time, it makes us think about the extent to which we are, even today, guided by the predictions and expectations of the past.

It is, I believe, only in knowing what our forebears anticipated, dreamed of and hoped for that we can begin to understand how we have ended up where we are. In conversing with the past, I have a deeper appreciation for the journey that we continue to make. Making sense of the transformative processes out of which modernity struggles to emerge is not only a means of interpreting the present but it is also a very powerful tool in making the future what we have long hoped it might be.