Before five shark attacks left four people dead and one wounded on the Jersey Shore in 1916, there was widespread doubt a shark would even bite a human.

But the attacks that occurred July 1-12, later dubbed “the 12 Days of Terror,” marked a major turning point in the relationship between sharks and humans that put the fish on the defensive and continues to threaten their existence a century later.

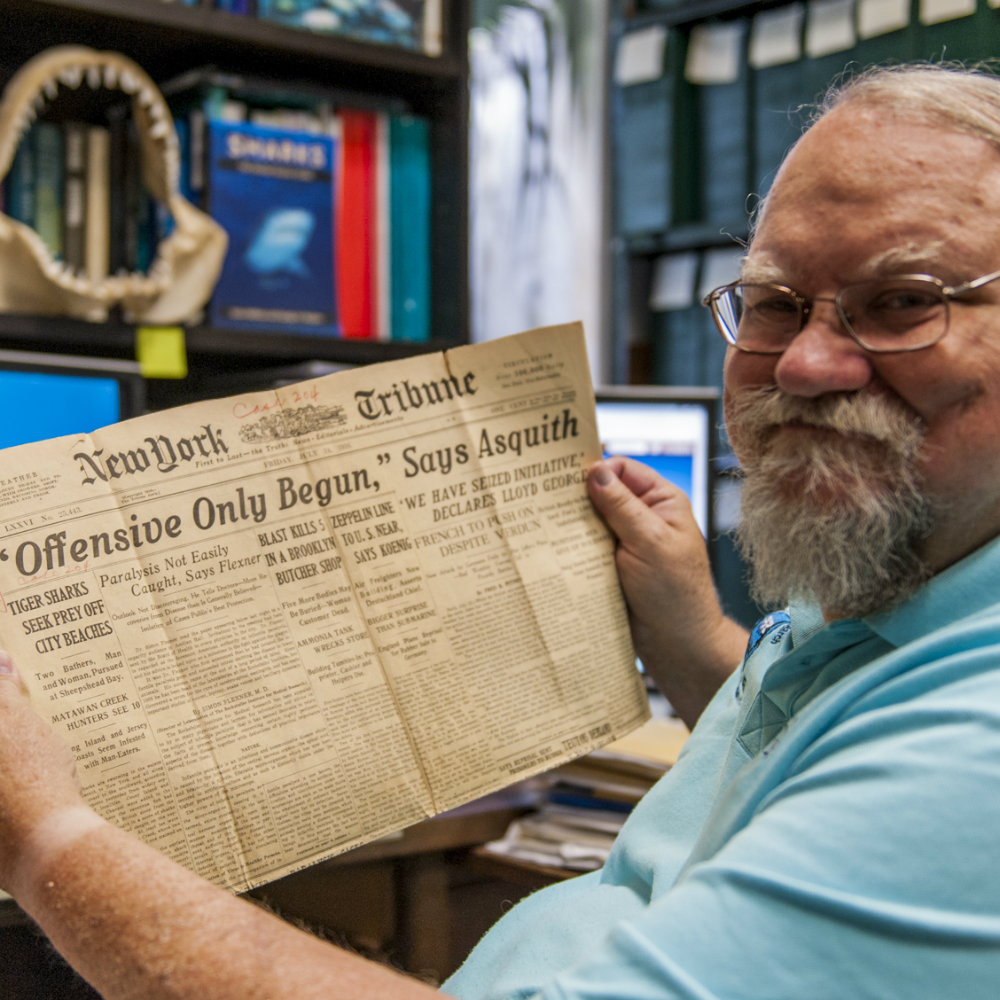

“It literally landed on the desk of the president,” said George Burgess, who directs the Florida Program for Shark Research and International Shark Attack File based at the Florida Museum of Natural History on the University of Florida campus. “It was affecting everybody.”

The Jersey Shore was a vacation hotspot, and during a polio epidemic and sweltering heat wave in 1916, thousands flocked to the seaside paradise.

The first two attacks happened on the coast, and the last three in Matawan Creek. Some experts suspected a bull shark, because it's the only shark that regularly swims into brackish water.

But the attacks occurred during a nearly full moon high tide when the tributary had maximum salinity. The high tide, severity of the human injuries and the fact a great white shark was later caught with human remains in its stomach, led Burgess to believe it was a great white.

And it was a 25-foot great white that spiked viewers’ heart rates in the 1975 film “Jaws.”

“When the movie came out, there was a collective testosterone rush up and down the East Coast,” Burgess said. Fishermen wanted to prove their bravery, and catching 500-pound sharks was possible with a reasonable size rod and reel.

Fishing tournaments offered prizes for sharks, and in the 1980s, commercial swordfishing increased, which Burgess said resulted in more shark catches. When swordfishing collapsed, fishermen marketed sharks, and the shark-fin trade skyrocketed.

The drop in sharks presented a long-term problem, Burgess said. Sharks are slow-growing, reach sexual maturity at a late age and give birth only every two to three years--meaning declines could require decades to bounce back.

Sharks play a crucial role in ocean biodiversity and ecosystems because they feed on sick as well as healthy animals.

“The beginning of the end was ‘Jaws,’” Burgess said. “The end of the end was commercial fishing.”

Burgess said humans kill 30 million to 70 million sharks each year, with some estimates as high as 100 million.

Most sharks are highly migratory, which makes enacting laws to protect them difficult.

“Sharks don’t honor geopolitical borders,” Burgess said. “We’re talking about a worldwide problem.”

Though in decline worldwide, U.S. shark populations are slowly recovering due to state and federal laws.

Burgess is hopeful if people work together to change public perception, the popular view might stray from the “Jaws” image toward what he thinks when he hears “shark”: a threatened predator that needs our help to survive.