Michael Gannon, who taught at UF for more than 30 years and was a nationally recognized historian – especially in matters related to Florida history -- passed away Monday at age 89. This article, which appeared in the Winter 2011 issues of “Florida,” then the UF alumni magazine, covers his long, rich and purposeful life.

It was a balmy evening in May 1972, and all around Michael Gannon* (PhD ’62) a nightmare was unfolding.

Florida highway patrolmen clad in riot gear were chasing UF student protestors down West University Avenue. Gannon, chaplain of the nearby St. Augustine Catholic student center, spotted a plate-glass-lined Krystal Hamburger restaurant packed to the gills with students seeking a safe haven. A state trooper was holding open the front door, his arm cocked as he prepared to lob a tear gas canister inside.

Gannon grabbed his arm and pleaded, “Sir, you do not want to throw that gas canister in there. If you do, those young men and women are going to be killed and maimed going through the glass.”

Seconds later, another trooper saw the altercation and whacked the priest with a nightstick. Gannon fell and was arrested. A UF official intervened for his release.

The canister was not thrown.

“I put myself in the middle of that to try to keep people from getting hurt,” Gannon recalls nearly 40 years later.

That devotion to students is a big part of what has made Gannon a UF institution, but that’s only part of the story. Among the other roles he’s filled are prize-winning author, mediator, historian, radio announcer, sports columnist, college professor and war correspondent.

“Mike has a particular talent at capturing what we all feel and reflecting the best of all of us,” says David Colburn, director of the Reubin O’D. Askew Institute on Politics and Society at UF and a member of the history faculty since 1972.

The Writer

Born in 1927 in Fort Sill, Okla., Gannon, his two younger brothers and his recently widowed mother moved to St. Augustine in 1940.

While still in high school at St. Joseph Academy, Gannon became a sports writer at the St. Augustine Record. World War II was in full swing, and the sports editor, Harvey Lopez, was called away to military service. At 16, Gannon took over the job.

The work meant missing class each afternoon to write and lay out pages. The sisters were none too pleased and told his mother. The truancy continued. Finally, Gannon was summoned by the Rev. Joe Devaney, assistant pastor at the Cathedral of St. Augustine.

In the 1970s Gannon was often a calming influence at UF amid student protests. Students, administrators and sometimes -- but not always -- law enforcement officers tended to trust his guidance.

Gannon braced himself for a tongue-lashing. What he got instead changed his life.

“Mike, I’ve been reading your stuff,” Devaney told Gannon. “It’s good but … your style is too ornate. You need a cleaner, more direct style. So I’m going to get you a subscription to the New York Herald Tribune so you can read (famed sports writer) Red Smith.”

He instructed Gannon to rewrite Smith’s column verbatim on his own typewriter.

“I want you to pay attention to the leanness of his style and how much he can say without using adverbs and adjectives,” Devaney told Gannon. “I want you to catch the rhythm of it.”

“God bless him,” Gannon says, “he taught me how to write!”

Recalling that event nearly seven decades later, Gannon’s eyes fill with tears and his ringing, baritone voice breaks.

“I always get choked up when I think about it. Here was a guy who’s in a position to scold you and he doesn’t. The guy made only $30 a month and he buys me a subscription.”

The lesson stayed with Gannon. He has authored numerous books, most of them focusing on Florida history. “Florida: A Short History” and “The New History of Florida” are considered must-reads for those interested in the state’s past.

Last March, in fact, the body of Gannon’s work earned him the inaugural Florida Lifetime Literary Achievement Award from the Florida Humanities Council.

The Priest

At 18, Gannon joined the American Field Service, but before he could begin training, the war was over. Without any clear goal in mind, he decided to try his hand at radio and spent the next four years giving play-by-plays of Southern college football.

With the radio bug out of his system, Gannon finally found the path he’d previously lacked: He decided to become a priest.

After graduating from Université de Louvain in Belgium, he was ordained in 1959. His first assignment: chaplain of the brand-new St. Augustine Catholic Church and Student Center in Gainesville.

“I organized the dedication ceremonies,” he says.

Gannon’s reach stretched beyond his church’s walls. For 12 years at the Catholic Student Center post — through the Kennedy assassinations, the Vietnam War, integration and campus strife — Gannon was a sounding board for students of all faiths on a host of issues.

It probably didn’t hurt that he, too, was a member of the UF community. Having earned his doctorate in history in 1962, he joined UF’s faculty in history and religion in 1967.

The War Correspondent

In the turbulent ’60s, no issue was so vexing to students as the war in Vietnam. After being asked countless times whether the war was moral, Gannon decided to find out for himself.

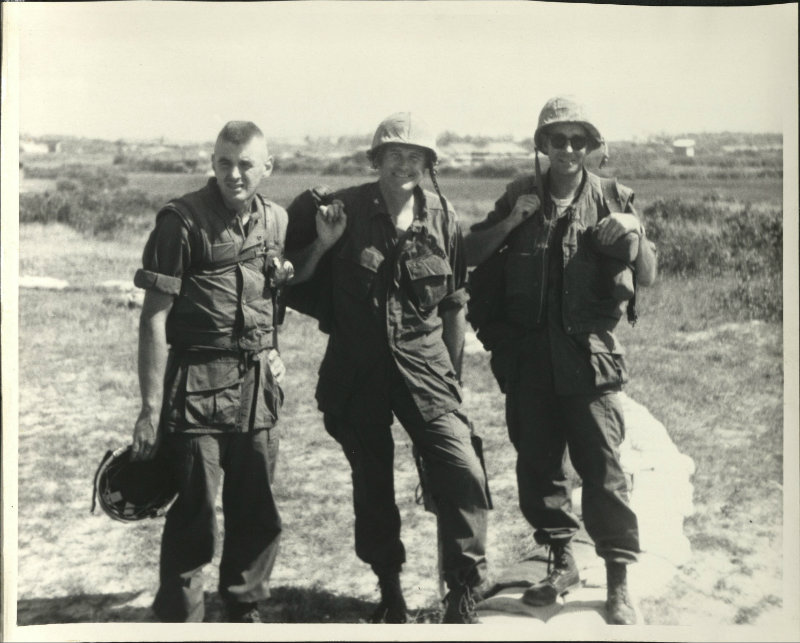

In the 1960s, Gannon questioned whether the Vietnam War was a just war. A former newspaper writer, he decided to go to Vietnam to see for himself.

Armed with a press pass from the national Catholic journal, America, Gannon spent a month in 1968 traveling the war-torn country from the Demilitarized Zone to the Mekong Delta. His journalistic duties were interspersed with his priestly obligations. More than once, he administered Last Rites to dying soldiers.

His conclusion: The war was not just. Not long after Gannon returned, war protests arrived on UF’s campus.

“In 1970, ’71 and ’72, we had student demonstrations the likes of which this old staid, Southern institution had never seen,” he says.

The first was May 4, 1970, hours after National Guardsmen shot and killed four Kent State students. Gannon led about 6,000 students on a march to the home of then-UF President Stephen C. O’Connell* (BSBA ’40, LLB ’40). They carried candles and sang John Lennon’s refrain, “All we are saying, is give peace a chance.”

The group found the house ringed by police. Gannon asked that the students be allowed to protest peacefully, “and that’s just what happened,” he says.

“[Gannon] had a good heart and a good mind. He was trustworthy. He was always interested in both sides,” says Steve Uhlfelder* (BSBA ’68, JD ’71), UF’s 1970 and ’71 student body president, now 63 and a Tallahassee attorney. “In my heart, I think he agreed with us more than [with] the administration.”

Yet Gannon was able to maintain the respect and trust of administrators, too. UF Trustee Cynthia O’Connell, wife of the late President O’Connell, has fond memories of Gannon.

“Michael was one of Stephen’s dearest and closest friends,” she says. “They had a love and respect for each other. Michael is a hero … he has always been a champion for the university, for the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, for students, for all things that are right.”

The Academic

In 1976 Gannon left the priesthood. He married, taught at UF full time and spent the next 30 years earning his academic stripes.

Gannon is widely respected for his research into colonial Spanish Florida — an interest spurred, in part, by his upbringing in St. Augustine.

Gannon gained widespread respect for his research into the development of colonial Spanish Florida, including the introduction of Catholicism — and Christianity as a whole — to the United States through St. Augustine.

Yet he stayed close to students, too, teaching an estimated 16,000 in 36 years at the university. He retired as a professor emeritus of history in 1998, but continued teaching until 2003.

“Mike seems to turn up everywhere in recent UF history,” says university historian Carl Van Ness* (MA ’85). “In May of 1970, he’s a calming force on campus after the Kent State shootings and delivers an eloquent and moving memorial to the four slain students. Thirty years later, he delivers the 9/11 memorial and somehow finds a way to reassure the campus … He is also a warm and caring person and one of the nicest people I have ever met.”

The “Retiree”

Since his retirement, Gannon has maintained a rigorous schedule of speaking engagements. And, of course, he writes.

His historical interests have turned toward World War II. He has written or edited 11 books so far, including “Black May,” “Pearl Harbor Betrayed” and “Operation Drumbeat.” He’s working on book No. 12 now.

Gannon, who received the LeRoy Collins Lifetime Leadership Award last summer, hasn’t forgotten the lesson in brevity his school administrator gave him as a cub sports reporter. One of his latest books revisits his popular lecture: “Michael Gannon’s History of Florida in 40 Minutes.” It’s just 80 pages long.

“I’d like to be remembered as a good person,” he says, then pauses. “Actually, I’d like to be remembered as a good writer.”

Michael Gannon is quite the character. In the 2011 winter issue of Florida, the historian and Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Florida reminisces on the many roles he has assumed during his interesting life. Gannon speaks of his time as a student, a professor, a war correspondent, and a priest. But there was one story that was too good to miss: how he met the 35th President of the United States. We include it here

Meeting President Kennedy

Michael Gannon met President John F. Kennedy at MacDill Air Force Base in Tampa days before the president's assassination. Photo courtesy of Michael Gannon

President John F. Kennedy was scheduled to visit MacDill Air Force Base in Tampa on Nov. 18, 1963. Harold Colee, then director of the Florida Chamber of Commerce, asked Gannon to meet with Kennedy and chat him up about St. Augustine’s upcoming 400th anniversary in 1965.

A 15-minute meeting between Kennedy and Gannon was arranged. With them were a White House photographer, a Tampa Tribune photographer and U.S. Secret Service Agent Gerald Blaine.

Gannon presented Kennedy with a framed copy of the oldest written record of American origin from 1565.

“He was fascinated, particularly since St. Augustine was a port,” Gannon says. “He wondered about the sandbars at the entrance to the port and so on … and he had a very solid knowledge of American maritime history.

“The last words he said to me were, ‘What did you say your name was?’ I said, ‘Michael Gannon,’ and as he turned to leave he said, ‘I’ll keep in touch.’ But four days later, he was dead. Four days.”

Two months later, Gannon received a package from the White House. Inside was a photograph of Gannon and Kennedy looking over the framed gift Gannon had given Kennedy. With it was a typewritten note from Blaine expressing how much the president had enjoyed his visit with Gannon.

“It was very touching that he did that,” Gannon says.