A UF religion scholar traces the history of “Eastern” religions in the West during the week marking the death anniversary of the Indian guru who brought transcendental meditation to the United States.

Vasudha Narayanan, University of Florida

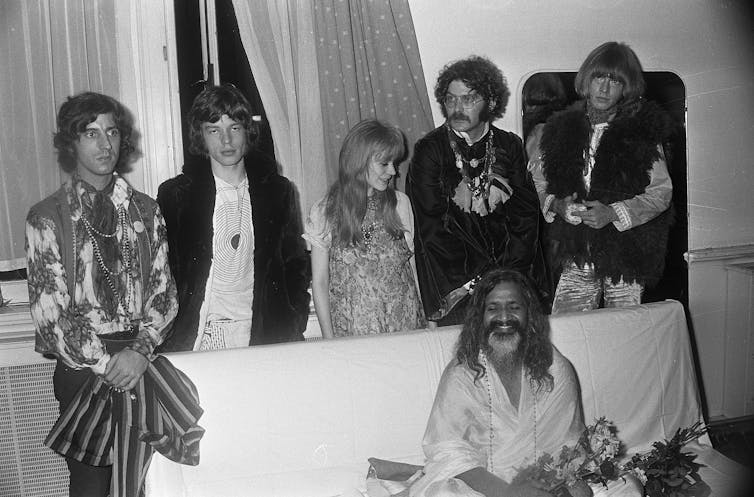

This week marks the death anniversary of Mahesh Yogi, the Indian guru who brought transcendental meditation to the West in the sixties and became a spiritual teacher to The Beatles, comedian Jerry Seinfeld and countless other celebrities.

Today, the legacy of the Maharashi, as he was popularly known, is evident in the widespread appreciation of meditation: Over 6 million people worldwide practice the technique the Maharishi introduced – transcendental meditation. An even larger number practice other forms. Health professionals and practitioners extol its many benefits, which range from anger management, lowered blood pressure and cardiovascular disease, reduced post-traumatic stress and simply a healthier lifestyle.

In the 1960s many Americans may have only known Hinduism through meditation, but the story of this country’s relationship with Hinduism is much longer and more complex.

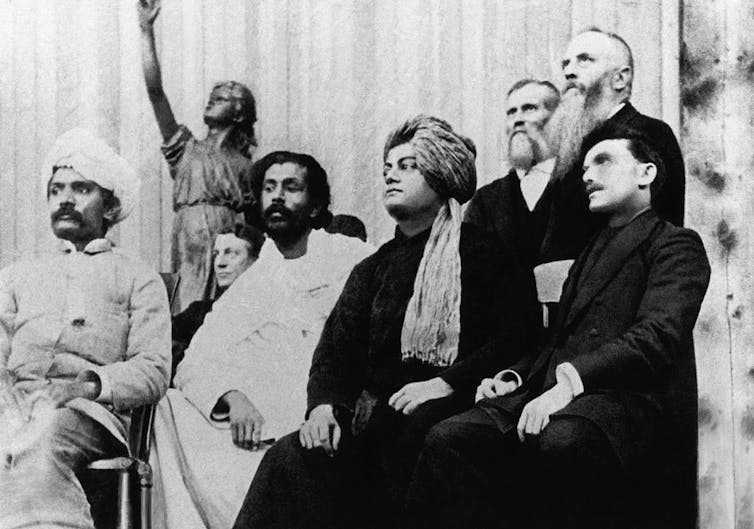

The first time the American public formally learned about Hinduism was through the World’s Parliament of Religions, a gathering of practitioners of different faith traditions, which took place in Chicago in 1893. It was at that time when the American public first saw and heard people from “Eastern” religions, including Hindus and Buddhists, on their own soil.

At the time European and American scholars were becoming more accepting of other major religions in the world. Not considered as good as Christianity, they were nonetheless being included in the roster of an emerging group of “world religions.” Unfortunately, no representative of any Native American traditions or indigenous religions was invited.

Vivekananda, a young monk representing Hinduism famously began his speech hailing his hosts as “brothers and sisters of America.” It was most unusual for an Indian monk to embrace the audience as a single family, at a time when societies were segregated and racial superiority was an accepted part of life. Vivekananda received a standing ovation. The appreciation continued as he journeyed through America after the talk. One journalist wrote:

“Vivekananda’s address before the parliament was broad as the heavens above us, embracing the best in all religions, as the ultimate universal religion—charity to all mankind, good works for the love of God.”

Vivekananda spoke extensively about the spiritual benefits of yoga and meditation, explaining how they were common resources for all human beings, and not just for Hindus.

“Think of a space in your heart and in the midst of that space think that a flame is burning. Think of that flame as your own soul and inside the flame is another effulgent light, and that is the Soul of your soul, God. Meditate upon that in the heart.”

In fact, long before the World’s Parliament of Religions, American transcendentalists, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry Thoreau, showcased their fascination with Hindu texts in their poems and essays. Emerson copied long passages from Hindu texts in his journals and called the Bhagavad Gita, a Hindu text composed approximately 2,000 years ago, a “trans-national book.” Emerson’s poems, “Brahma” and “Hamatreya,” modeled on passages from Hindu texts speak about the impermanence of life and the immortality of the human soul.

Indeed, their adulation has assured the presence of the Bhagavad Gita in most large libraries in the United States.

Since the 1960s, two kinds of Hinduism have made their home in the U.S.

One is a continuation of the popularization of meditation started by Vivekananda and Mahesh Yogi. Many other gurus came from India during the sixties and taught self-transformation through yoga and meditation. This acquired such popularity that Life magazine called 1968 the “year of the guru.”

In more recent years, Deepak Chopra, who was once a disciple of Maharishi, brought the meditation-body-mind healing to American consciousness. This work has made Chopra a popular author, public speaker and advocate for complementary healing in America today.

Some, though not all, of these movements underplay or distance their connections with the word “Hindu” and some use labels such “spiritual” to emphasize their “universal” content.

In other words, though the teachers were Hindu and their teachings had Hindu origins, they were presented not as Hindu or as “religious,” but in a generic form as “spiritual” and as applicable to all human beings.

Meditation advocated by these gurus became distanced from its religious roots. In India, meditation, especially on a mantra (a syllable, sound, word, or phrase), is only one part of the larger Hindu culture.

Conservative estimates by the National Institute of Health show that over 18 million Americans meditate and approximately 21 million adults and 1.7 million children practiced yoga regularly. Interestingly, although some Americans may associate meditation with Hinduism, another set of data shows that more than half the Hindus in America never practice it.

Movies too have embraced Hindu ideas. For example, “the Force” in “Star Wars,” has parallels with Hindu philosophical ideas such as “Brahman,” the Supreme, the ultimate principle of the universe, as does the illusory overlay in “The Matrix,” with “Maya,” the wondrous illusory power. It’s no accident that the creator of Star Wars, George Lucas, learned from Joseph Campbell, who was a student of Hindu-Vedanta philosophy.

The second kind of Hinduism that has grown in America since the 1960s is what I would call “temple-Hinduism,” brought by immigrants from India and the Caribbean.

In 1900, seven years after Vivekananda set foot in America, there were only about 1,700 Hindus. Today, there are about 2.4 million Hindus who have made America their home today. Many of the current immigrants came following a new immigration law enacted in 1965 that abolished a quota system.

The new immigrants wanted to practice of their faith centered on rituals done in temples at specific days and times with processions, dances and music. Meditation was only one part of it.

![]() Thoreau could have hardly imagined that within 150 years of his meditations, the waters of the Ganges in India would be mingled with waters of Walden to consecrate the temple of the Goddess Lakshmi in Ashland, Massachusetts, in 1989, and hundreds of temples across America.

Thoreau could have hardly imagined that within 150 years of his meditations, the waters of the Ganges in India would be mingled with waters of Walden to consecrate the temple of the Goddess Lakshmi in Ashland, Massachusetts, in 1989, and hundreds of temples across America.

Vasudha Narayanan, Distinguished Professor, University of Florida

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.