A UF researcher who specializes in infectious diseases explains why norovirus occurs so frequently and why it’s so difficult to contain.

Kartikeya Cherabuddi, University of Florida

Editor’s note: At the Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang, South Korea, there have been more than 200 confirmed cases – mostly security and games personnel, but also two athletes. We asked Kartikeya Cherabuddi, an infectious disease expert at the University of Florida, to explain what this virus is and how it spreads.

What do the Olympics, cruise ships and nursing homes have in common? They all involve humans congregating in a small area – creating a comfortable environment for norovirus outbreaks.

Norovirus is a very contagious virus. It’s a common cause of gastroenteritis, or inflammation of the intestine, worldwide.

The symptoms start as abdominal cramps and nausea. Vomiting – more common in children – and diarrhea – more common in adults – can also occur. About half of cases involve a low-grade fever around 100.5°F.

Some people have no symptoms. In fact, as many as one-third of infected people show no symptoms but still pass the viruses in the stool.

Norovirus spreads from an infected person mainly by direct contact (such as shaking hands), by touching an infected surface or though contaminated water and food. Seven in 10 of all contaminated food related norovirus outbreaks are caused by infected food workers.

Norovirus can cause serious illness and even death in children under the age of five, as well as the elderly and people with weakened immune systems. In otherwise healthy people, including athletes, it could cause dehydration and significant discomfort.

There’s no specific treatment. Doctors typically support patients by providing oral and intravenous fluids. The good news is that there are no long-term complications. Recovery is quick, usually in 72 hours.

Outbreaks tend to terminate spontaneously in one to two weeks.

Norovirus infections can spread quickly.

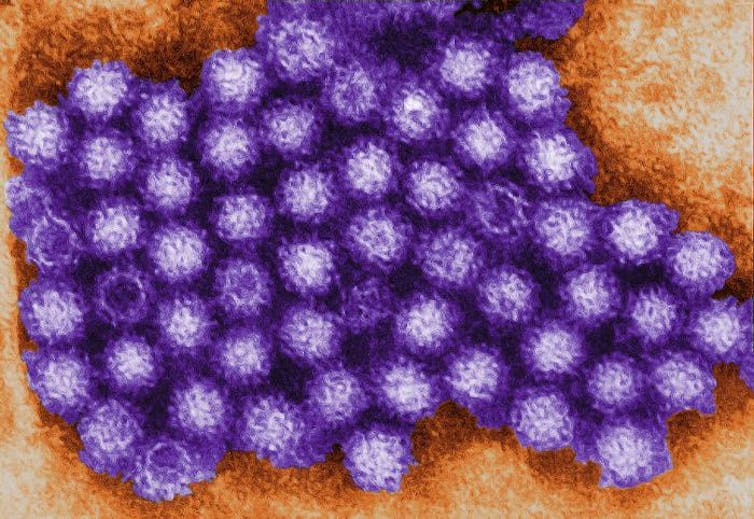

A very small amount of norovirus – as low as 18 individual viruses – can lead to infection. Norovirus also has a high “secondary attack rate,” meaning that 30 percent of people who are exposed become infected. There is no vaccine.

Like the flu, norovirus has many different strains. Prior infection does not provide immunity and using alcohol sanitizers alone cannot prevent its spread. It can also survive on environmental surfaces and is tolerant to freezing and heat up to 140°F.

The Olympic tend to have closed areas with communal dining where a number of people interact with each other. All of these factors enable the infection to spread quickly in 24 to 48 hours, affecting many people.

What’s more, norovirus outbreaks predominantly occur in the winter for reasons that aren’t entirely clear. In a study done in England and Wales, the peak of winter was significantly associated with norovirus outbreaks in health care facilities.

The South Korean government took steps to prevent the outbreak, including quarantining security staff; inspecting the hygiene at restaurants and accommodation venues; and testing tap water and drinking sources.

But that may not have been enough to stop the outbreak. The virus could have been present in other people who showed no symptoms.

Norovirus infections are not easy to diagnose. Though infections are very common, they’re often not attributed to norovirus because testing is not widely available.

So: It’s winter. An unprecedented number of young people in tight-knit groups are living in closed spaces. They’re serviced by a large number of people temporarily mobilized to meet their needs. They’re confronted with a microbe that appears to be custom-made for such a situation – a microbe to which they have no real immunity and whose diagnosis tends to be delayed. It’s remarkable that the virus didn’t spread farther than it already has.

Illness outbreaks – of norovirus or of other infections – are common whenever large groups of people come together. For example, at the 2012 London Olympics, 310 of the 10,568 athletes had a respiratory illness and 123 had a gastrointestinal illness.

Organizers have to pay an extraordinary amount of attention to food and water safety, as well as sanitation. They have to communicate constantly as the situation evolves.

People attending these gatherings also have to take precautions. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website is a great resource for travel-related advice. At the University of Florida travel clinic, we ensure that people receive the right vaccines and prophylactic medications, as well as offer advice on safety, sanitation and hygiene.

To prevent norovirus infections, people should wash their hands thoroughly with soap and water and use alcohol sanitizers, which can be helpful for other infections. Avoid cold foods that require handling, like salads, sandwiches and oysters. If infected, do not prepare food for others for two days even after you feel well.

![]() Finally, at the cost of appearing rude, do not shake hands – wave!

Finally, at the cost of appearing rude, do not shake hands – wave!

Kartikeya Cherabuddi, Physician, University of Florida

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.