A UF religion scholar discusses a religion that influenced Judaism, Christianity and Islam, and that despite its small numbers, counts famous musicians, scientists, scholars, artists and entrepreneurs among its ranks.

In the Freddie Mercury biopic, “Bohemian Rhapsody,” there’s a scene in which a family member scolds Mercury.

“So now the family name is not good enough for you?”

“I changed it legally,” Mercury responds. “No looking back.”

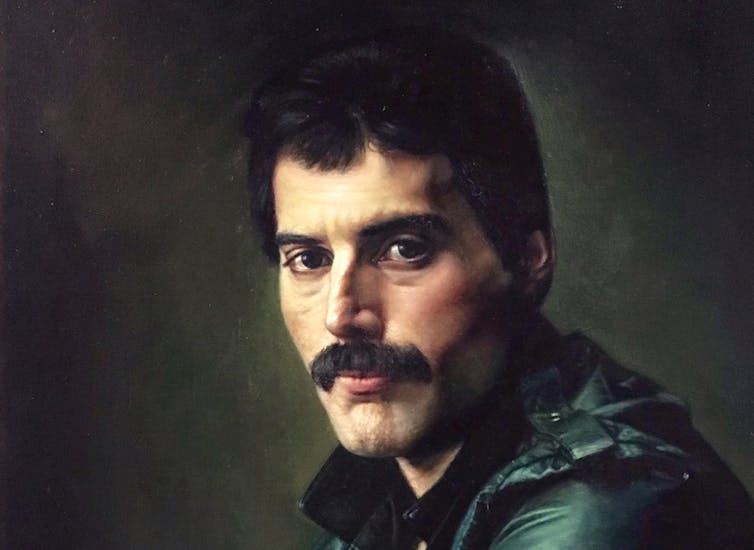

It might come as a surprise to some that Freddie Mercury was born Farrokh Bulsara. He came from a Parsi family that had roots in India and he was a Zoroastrian by faith.

In the world religion courses I teach at the University of Florida, we discuss Zoroastrianism.

Fleeing religious persecution from Muslims in Persia sometime between the seventh and 10th centuries, the Zoroastrians settled in India, where they came to be called “Parsis.”

Like Freddie Mercury, they worked to integrate into their new surroundings. Yet they also stayed true to the values, beliefs, and practices of their religion, which many scholars say had an influence on Christianity, Islam, and Judaism.

The Zoroastrian faith is one of the world’s oldest religions, one that could date back as far as 1200 B.C.

Zoroaster, a prophet who lived in modern-day Iran, is viewed as the founder of Zoroastrianism.

We’re not sure when Zoroaster lived, though some say it was around 1200 B.C. He is thought to have composed the Gathas, the hymns that make up a significant portion of the Yasna, which are the liturgical texts of the Zoroastrians.

According to the Zoroastrian tradition, Ahura Mazda is the supreme lord and creator; he represents all that is good. In this aspect, the religion is one of the oldest examples of monotheism, or the belief in one god.

The main tenets of the faith center on the opposition between Ahura Mazda and the forces of evil which are embodied by Angra Mainyu, the spirit of destruction, malignancy and chaos. This evil spirit creates a serpent named Azi Dahaka, a symbol of the underworld, not unlike the Biblical serpents of Judeo-Christian traditions.

Within this cosmic battle we see the tension between “asha,” which roughly translates to “truth,” “righteousness,” “justice” or “good things,” and “druj,” or deceit.

Truth is represented by light, and Parsis will always turn to a source of light when they pray, with fire, the sun and the moon all symbolizing this spiritual light.

Indeed, scholars have noted the strong historical influence that Zoroastrianism has had on concepts seen in Judaism, Christianity and Islam, whether it’s monotheism, the duality of good and evil, or Satan

Today Zoroastrianism has a small but devout following, though it’s been shrinking.

In 2004, it was estimated that there were between 128,000 and 190,000 Zoroastrians living around the world, with 18,000 residing in the United States.

The “Qissa e Sanjan,” which translates to “The Story of Sanjan,” was composed around the 17th century. It describes how the Zoroastrians, fleeing religious persecution from Muslim invasions in their Persian homeland many centuries earlier, head to Gujarat, in western India.

Once they arrive, they reach out to the local king, whom they call “Jadi Rana.” He agrees to give them land if they adopt local dress, language and some customs. However there is never any question about religious faith: They still practice their religion, and Jadi Rana is elated that these newcomers worship as they please.

Parsi history has two versions of what took place.

In one, when the Zoroastrian refugees arrived in Gujarat, the king sends them a jar of milk filled to the top – his way of saying that his kingdom is full and there’s no room for any more people. In response, the newcomers stir in a spoonful of sugar and send it back to the king. In other words, not only do they promise to integrate with the local population, but that they’ll also enhance it with their presence.

In the other version, they drop a gold ring into the bowl to show they’ll retain their identity and culture, but they’ll nonetheless add immense value to the region.

These are both compelling narratives, though they make slightly different points. One extols the integration of immigrants, while the other highlights the value of different cultures living together but in harmony.

Parsis in India – and wherever they have gone – have done both. They’ve adopted some of the customs of the land they live in, while maintaining their distinctive culture, religious rituals, and beliefs.

They’ve also made more cultural contributions than the initial wave of refugees to Gujarat could have ever imagined.

Despite their small numbers, Parsis can count a number of famous musicians, scientists, scholars, artists and entrepreneurs among their ranks.

Beyond Freddie Mercury, there’s Zubin Mehta, the director of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra; Jamshedji Tata, founder of the Tata Group, the largest business conglomerate in India; Dadabhai Naoroji, the first Indian elected to the British Parliament; Harvard professor Homi K. Bhabha; and nuclear physicist Homi J. Bhabha, to name a few.

Freddie Mercury’s family were migrants. Their first home was in India. Then they moved to Zanzibar, before finally settling in England.

Like his ancestors, Freddie Mercury integrated into a new culture. He changed his name, and became a Western pop icon.

Yet through it all, he remained immensely proud of his heritage.

“I think what his Zoroastrian faith gave him,” his sister Kashmira Cooke explained in 2014, “was to work hard, to persevere, and to follow your dreams.”![]()

Vasudha Narayanan, Professor of Religion, University of Florida

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.