The ancient Maya are not particularly known for their love of freshwater mussels. Mathematics, maize, pyramids and human sacrifice, yes. But bivalves? Not so much.

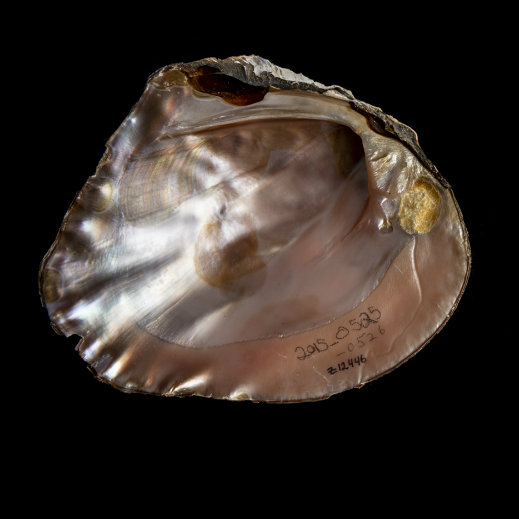

Yet Florida Museum of Natural History archaeologists Ashley Sharpe and Kitty Emery could not sift through a single bag of material from their dig sites near the Mexican-Guatemalan border without turning up mussels: discarded shells from meals, shells used as paint pots, shell pendants, shell discs sewn into clothing like iridescent sequins and ground shell powder that may have been an early form of glitter. They even found corpses carefully buried with bivalves clasped in their hands.

But when Sharpe and Emery documented their findings, they ran into a problem – matching the right name to the right mussel species.

“Either no one had given names to them or we had the problem where naturalists had given 50 different names to one thing,” said Sharpe, a University of Florida doctoral graduate and now a research archaeologist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. “We could tell the Maya were identifying different types of mussels and using them in different ways, but I would end up just referring to them as ‘mussel a’ and ‘mussel b.’”

To read the full article, click here.