The University of Florida commemorated 60 years of desegregation with a ceremony honoring George Starke Jr., UF’s first African-American student.

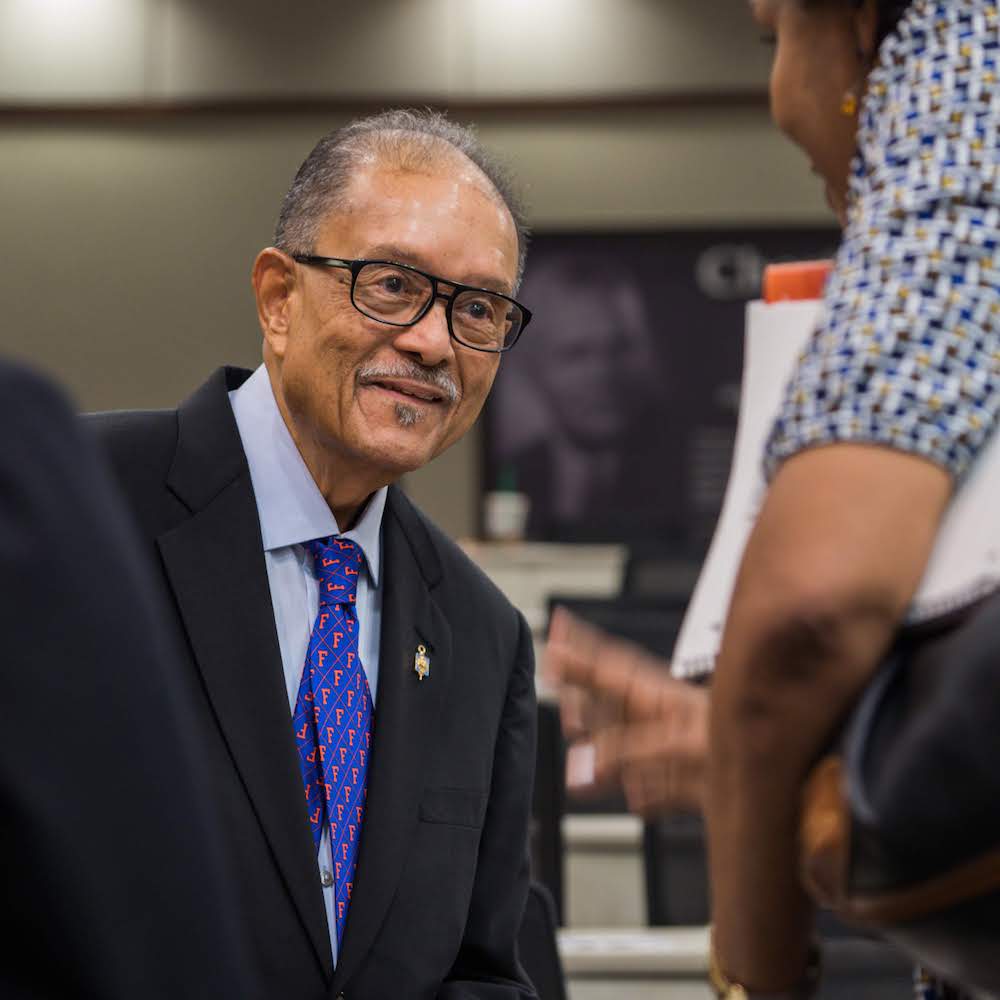

Starke, pictured above, enrolled as a law student in 1958 and returned to UF Nov. 7 to reflect on his experience and his legacy.

“George Starke blazed a trail that our students still follow today,” said UF Levin College of Law Dean Laura Rosenbury. “He broke barriers not for his own benefit, but for the benefit of those he would never meet.”

The event, organized by the college’s Center for the Study of Race and Race Relations, also honored Virgil Hawkins, who was denied admission to UF in 1949 because of his race and fought the decision for nine years. The United States Supreme Court ruled that Hawkins should be admitted without delay, but the Florida Supreme Court still refused. Hawkins, who died in 1988, eventually withdrew his application in exchange for the desegregation of UF’s graduate and professional schools.

Dean Rosenbury thanked the Hawkins and Starke families and recognized Judge Stephan Mickle, who in 1965 became the first African-American student to earn an undergraduate degree from UF. Mickle, a 1970 UF Law grad, attended the event.

“Your families and so many other families in the state of Florida endured a terrible injustice when the state refused to admit so many promising students solely because of their race,” Rosenbury said. “We will never be able to erase that injustice. It lives with us.”

“We owe Mr. Starke and Mr. Hawkins and their families a deep debt that we can never repay,” she said, pledging to “recruit the best and most diverse law students from all walks of life.”

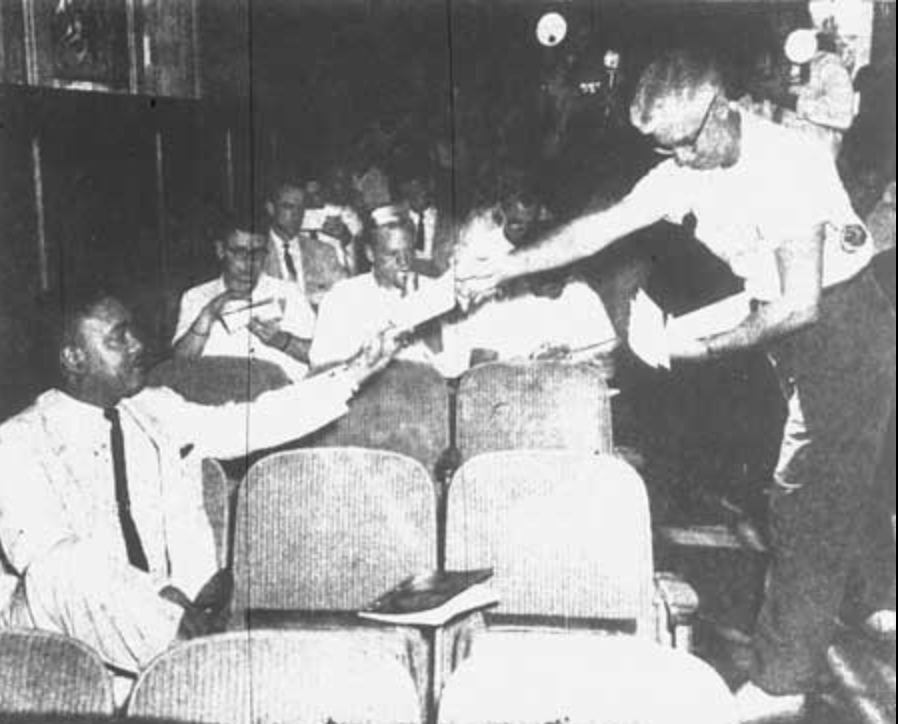

George Starke Jr. receives a registration packet on his first day of classes at UF, Sept. 15, 1958. Photo from the Gainesville Sun via the UF Libraries.

Katheryn Russell-Brown, the Chesterfield Smith professor of law at UF and director of the center, said the event was designed to educate, inspire and spark conversation about race relations at UF past and present while celebrating Starke’s contributions.

“It took courage and faith in the unseen for him to apply to a university that had never before admitted a black student,” Russell-Brown said.

Katheryn Russell-Brown, a UF Law professor and director of the UF Center for the Study of Race and Race Relations, introduces George Starke at the event.

Stepping to the microphone to a standing ovation, Starke reflected on the hardships borne by other pioneers of integration, saying he didn’t face the blocked doors, riots or violence they endured.

“The campus here was more like an oasis,” he said. “You didn’t feel the pressures of other students that were first at their colleges and universities.”

But Starke didn’t have an easy road at UF. In archival video of his first day of class, the tension is palpable.

Undercover law enforcement officers guarded him in class and in the library to protect him from violence. He faced hostility from professors and administrators. At Thanksgiving break, he had to re-route his trip home to the Orlando area to avoid threats from the Ku Klux Klan. Eventually, the stress became overwhelming, and Starke left UF, going on to become a consultant and business owner in the finance and energy industries.

In her remarks, president of the Black Law Student Association Courtney Handy acknowledged that the challenges faced by students of color continue.

“As black students on this campus, oftentimes we may feel that we don’t belong,” she said.

UF’s chief diversity officer, Antonio Farias, detailed the declining proportion of African-American students in Florida’s state universities, which has dropped from 18 percent in 1999 to 12 percent in 2018. (Only 6 percent of UF students are African American.) During the commemoration, Farias moderated a panel on race, law and desegregation with University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill law professor and former NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund president Theodore M. Shaw and UF historian Carl Van Ness. Van Ness described the climate of the UF campus in 1958, when “Dixie” played at football games and the Johns Committee challenged civil rights activists before turning its attention to the gay community.

Students who spoke at the gathering honored — and pledged to continue — the legacies of Starke, Hawkins, Mickle and W. George Allen, a 1962 UF Law graduate who was the first African-American student to receive a UF degree.

Ana Mata, the president of Students Taking Action Against Racism, recalled walking past photos of UF Hall of Fame members in the Reitz Union and noticing how, moving from the past to the present, the photos changed from solely white men to include women and minorities.

“This change would have never been possible without Mr. George Starke,” she said.

Akil Reynolds, president of UF’s Black Student Union, noted that 2018 also marks the 50thanniversary of BSU.

“I’m grateful to follow in the path they have created,” Reynolds said.

Law student Nikole Miller described her drive to continue forging that path.

“The fight is by no means finished,” she said. “I may or may not see a drastic change during my lifetime, but if I can inspire others the way that these men have inspired me, well, then, we can change the world.”

Those in the Gainesville area can experience another component of the anniversary celebration — an exhibition curated by Diedre Houchen, post-doctoral associate in the Center for the Study of Race and Race Relations, and Florence Turcotte of the UF Smathers Libraries in three locations on campus and in the community. At the Smathers Library Gallery, "Black Educators: Florida’s Secret Social Justice Advocates, 1920-1960" is on view until Dec. 18, as is an exhibition dedicated to the legacy of Virgil Hawkins at the law school's Lawton Chiles Legal Information Center. At the A. Quinn Jones Museum and Cultural Center off campus, "Lincoln High School: A Metaphor for Excellence" continues through June 30. Hours and visitor information available at https://education.ufl.edu/student-services/files/2018/10/Black-Educators-Press-Release-Final.pdf.