The challenges facing the natural world that sustains us are massive. So are the determination and ingenuity of University of Florida faculty, staff and students devoted to solving them.

Here, we highlight some of the people dedicating their careers to our well-being, paired with works from “The World to Come: Art in the Age of the Anthropocene” — an exhibition created by UF’s Harn Museum of Art.

If you’ve ever wondered what one person can do in the face of such overwhelming issues, read on and be inspired.

Artwork: "Oscar" from the series Terrain, 2012, by Jackie Nickerson, courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Artwork: "Oscar" from the series Terrain, 2012, by Jackie Nickerson, courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

"My dream is for food security worries to be something of the past.”

Research professor of tropical soil science, UF/IFAS

This World Food Prize Laureate works to reduce hunger while protecting the environment.

What keeps you going?

Sanchez led a team that tripled rice yields in Peru in the 1970s and has been instrumental in boosting corn yields in sub-Saharan Africa, which have nearly doubled since 2005. Farmers in more than 20 countries use the soil-improvement strategies he helped develop. “When a farmer comes to me and says, ‘Because of what you have taught us, my family is no longer hungry and I have my dignity restored’ — wow. That’s more important than all the honors I’ve gotten,” he says.

What concerns you about global food security?

“Political unrest. Under peaceful situations, farmers in Africa are doing a lot better.”

How do you stay optimistic?

“I see the results of our efforts. I never did any of these things alone. Most of the time I led a group of people and when I saw it was taking off, I drew back and let others do the leading. Now I see my students or colleagues rising into high places and taking over.”

What role do land-grant universities play?

“They’re essential in linking world food security and environmental sustainability. This university and the other land-grants know how to grow crops or livestock or trees in ways that have very little negative effect on the environment and get high yields in the process. What would happen if we didn’t have them?”

What impact to you hope to have in the long term?

“My hope is that in 20 years, we can say, ‘Remember when we were worried about food security in the world? Remember when nutrition was a concern? Remember when agriculture was damaging the environment?’ My dream would be that in most countries, this will be something of the past.”

Read more about Sanchez's journey in this column by Jack Payne, UF's senior vice president for agriculture and natural resources and leader of the Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Artwork: "Paradise on Fire IV, 2007, Paradise on Fire II, 2007, Paradise on Fire I, 2007, Paradise on Fire V, 2007" by UF College of the Arts professor Sergio Vega, courtesy of the artist

Artwork: "Paradise on Fire IV, 2007, Paradise on Fire II, 2007, Paradise on Fire I, 2007, Paradise on Fire V, 2007" by UF College of the Arts professor Sergio Vega, courtesy of the artist

“We can have conservation and development in the Amazon.”

Assistant professor, Department of Tourism, Recreation & Sport Management, College of Health and Human Performance

By using drones to get a bird’s-eye view of the Amazon and other key conservation areas, she’s helping sustainable tourism gain ground as an alternative to deforestation.

How can unmanned aerial vehicles help slow deforestation?

As co-director of the GatorEye Unmanned Flying Laboratory, Almeyda Zambrano is pioneering a faster way to gather data via 3D drone scans. “Typically, I would ask people about their forest and rely on those answers. But if I can quickly fly over it, I can get gigabytes of data on the quality of that forest — for example, how much carbon is it sequestering, or the area of secondary vs. old-growth forest, which is hard to map via questionnaire. My next step is to compare how ecotourism can result in environmental and social win-wins. The results will help enable long-term sustainability for these enterprises in the global tourism market.”

Why UF?

After getting her master’s degree from UF’s Center for Latin American Studies, Almeyda Zambrano went on to Stanford for her doctorate in anthropology and Harvard for post-doctoral work in sustainability science. “Those are amazing places with lots going on, but in terms of the number of researchers collaborating on interdisciplinary research in the Amazon, I don’t think there’s any place better than UF. Right now, I’m involved in a collaboration among faculty in wildlife, sociology, tourism and forestry. It’s really an outstanding collaborative environment.”

What do you want your students to understand?

“I would like them to see the development and conservation possibilities within the Amazon, including but not limited to tourism. There are many approaches to enhance sustainable development, and the key is to have the tools, the framework, to select from the suite of possibilities those that are most effective, cost efficient, and will result in long-term results. I would like my students to have the broad vision of what’s possible, so if they choose, can be positive players on the global stage.”

What gives you hope?

“The pace of deforestation in the Amazon continues to increase. New political dynamics only give rise to concern. However, there is hope and solutions are possible. I’m collaborating on studies on forest regeneration and recovery of ecosystem services. Another example is Costa Rica, which continues to lead the world for sustainable tourism. It’s by no means perfect, but working in areas that are leading as positive examples gives me hope for areas such as the Amazon frontier.”

What can we do?

“If you’re looking to have an adventurous vacation, I would definitely encourage you to look into certified sustainable hotels where you can get an authentic experience and support conservation as well as families at the same time. National Geographic also has compiled a list of unique lodges of the world. I hope to continue visiting these locations, as each presents an example of success in widely varying social, economic and ecological landscapes.”

Artwork: "Emerging from the Swamp" by Dana Levy, 2015, courtesy of the artist and Braverman Gallery

Artwork: "Emerging from the Swamp" by Dana Levy, 2015, courtesy of the artist and Braverman Gallery

"We can change, and it's up to us to do so."

Environmental fellow, The Bob Graham Center for Public Service; environmental journalist in residence, UF College of Journalism and Communications

This National Book Award nominee’s writing wraps environmental insight in appealing packages from rain showers to seashells, while her teaching spans civics and storytelling.

What will you explore in your book about seashells?

“I try to think about ways to draw the public to the story of the planet, and seashells are something we’ve always wanted to listen to. It’s sort of irresistible to pick a shell up to the ear and listen to what it’s trying to tell us — and they are telling us a profound story about what we’re doing to the ocean. The tiniest shells are beginning to disintegrate in the acidifying sea. It really is a metaphor for something much bigger.”

Turning points:

Barnett looks to UF legends Archie Carr, who brought international attention to the plight of sea turtles, and Frank E. Maloney, the Levin College of Law dean who helped write Florida’s model land and water laws in the early 1970s, as inspirations who helped lead society toward a more sustainable future. “We have a role beyond the classroom and beyond any specific books we’re writing or research we’re doing to set a tone for how we can live differently in Florida, in the United States, in the world. We’ve had these turning points in Florida’s history where the university has been really important to changing the ethos. We’re in one of those times now.”

What gives you hope?

Barnett finds hope in the students who seek her out. At the Graham Center, she teaches Environmental Leadership through biography. In her Environmental Journalism course, students publish a project grounded in solutions. “If you look back over our environmental history, there are terrific stories of big things that we turned around. Acid rain was a global crisis that required international cooperation, and it did happen. Those are the things I want people to remember and feel inspired about. The story of humanity is the story of renewal and readjustment. It often takes us way too long, but it’s important to remind people that’s what we do, and that’s what we are doing now.”

Why do you write to “the caring middle”?

“We know on issues such as climate change, there’s a core group of deniers who are never going to change the way they think, and that’s ok, because that’s only 7 to 10 percent of the population. There’s a core group of super-worried people who know exactly what’s happening. Then there’s a really large group in the middle, and those are the people science tells us we need to reach to be able to make a difference. I try to think of ways to appeal to that group that I think of as the caring middle. That’s why I like to write about a seashell rather than the words ‘ocean acidification’ that are kind of hard for people to swallow.”

What impact would you like to have?

“I hope I can help inspire a new ethic for the way we live with water, the climate, our earth.”

Read more about Barnett and other champions of the environment from the College of Journalism and Communications.

Video by Lyon Duong and Brianne Lehan/UF Photography. Artwork: "Paradise 14 Yakushima/Japan" by Thomas Struth, 1999, museum purchase, gift of Dr. and Mrs. David A. Cofrin

"Relationships really do matter."

distinguished professor and curator at the Florida Museum of Natural History; director, UF Biodiversity Institute

distinguished professor and curator at the Florida Museum of Natural History and UF Department of Biology

Understanding how we and other species fit into the interconnected web of life on Earth can hold the key to preventing disease, developing new medicines and predicting the impacts of climate change. That’s why Pam and Doug Soltis — members of the National Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences — and their collaborators have created a Tree of Life that maps the relationships between all living things.

Beyond its potential to advance science, the Soltises (sometimes referred to by colleagues as the Solti) wanted to take the Tree of Life to the general public as well, so they worked with Rob Guralnick, Associate Curator of Informatics at the Florida Museum of Natural History, as well as international artist Naziha Mestaoui and UF College of the Arts professor James Oliverio to visualize how all life is connected.

“One of the things we find really motivating is the opportunity to bring science and the arts together,” Pam says. “It would be great if people get excited about the beauty of biodiversity and start to work toward preserving and appreciating what we have on this planet.”

Artwork: "Untitled" by Sandra Cinto, 2015, courtesy of the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York

“Your home is your castle, and castles aren’t blown down by wind.”

Associate professor of civil and coastal engineering, Herbert Wertheim College of Engineering

Having the knowledge about how to protect homes from wind damage doesn’t help if homeowners don’t act on it. Prevatt looks at ways to take engineering knowledge to the public to safeguard life and property.

Rethinking wind:

“I’m a windsurfer and a sailor. As a kid, I was fascinated by how the wind could be harnessed to provide power to move us forward. I’m from the Caribbean, and the winds there also can be so destructive. It made me start asking, why? We choose to build in a particular way at a particular place that makes what we love vulnerable. As a structural engineer, I can build differently. I can build to be resilient. I can build to be stronger. I can build houses to be resistant to these wind effects.”

Why are homes still vulnerable?

Building codes in Florida have improved after Hurricane Andrew caused more than $20 billion in damages in 1992, but almost 80 percent of Florida’s current structures were built before then, so are likely to be vulnerable to wind damage. Retrofits — reinforcing of existing structures to make them stronger — can help, but are rarely implemented, Prevatt says, in part because homeowners don’t realize how vulnerable their houses are to wind damage or the how difficult rebuilding might be. “When you’re taking two kids to dancing class and soccer practice and trying to make your way in the world, you come home in the evening and it’s the last thing you want to think about. No one has attempted to provide homeowners with tips on how to resolve the dilemma of retrofitting.” Prevatt is looking at solutions, from understanding how homeowners make decisions to a mobile app that could identify the most effective retrofits and guide them through the process.

Homes of the future:

“Imagine if you were driving a car that was still based on 1950s technology. Now imagine living in a 1950s house. You don’t have to imagine it, because that’s what you’re living in right now. There has been almost zero innovation to the basic structural framing in single-family homes since the 1950s. It doesn’t have to be this way.” Pre-fabricated walls could offer a more affordable and wind-resilient alternative to traditional construction, Prevatt says. “You could buy your walls in Home Depot just as you buy lumber. We know how to do that, and it can solve some of these problems. As sustainability and wind-resistance become bigger issues, maybe as a society we might start coming together and thinking about it.”

What change would you most like to see?

"I’d hope to help our population understand that hurricanes are natural hazards — they are the way the earth breathes and controls its systems and therefore we ought not to try to change or control hurricanes. However, disasters are something we create and therefore can control. We create the disasters caused by natural hazards one building at a time. We have chosen to build in particular ways that are vulnerable, although we know better. We continue to migrate to coastal areas susceptible to hurricanes and bring our old, inadequate house construction techniques with us, only to be surprised that they don’t work. Ultimately, it’s up to us — collectively we can change outcomes. We can choose other approaches, but we have to do so as a community, and we have to make a long-term commitment to sustainable construction. The houses we build today will affect the vulnerability of our community for the next 50 to 70 years. As civil engineers, it is our responsibility to ensure you can find the construction technology so you won’t have to live with the uncertainty that the next hurricane is going to blow your house away.”

Hear Prevatt explain what hurricane-force winds feel like in this NPR clip.

Artwork: "Cape Coral, Florida #1, 2012" by Edward Burtynsky, 2012, courtesy of Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Artwork: "Cape Coral, Florida #1, 2012" by Edward Burtynsky, 2012, courtesy of Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

"We're trying to foresee the future."

associate professor, UF College of Design, Construction and Planning

professor, UF College of Design, Construction and Planning

Nearly 40 percent of the world’s population lives within 60 miles of a coast. These interdisciplinary architects are reimagining how we co-exist with water.

Cities of tomorrow:

As directors of the Center for Hydro-generated Urbanism, Kohen and Clark envision new types of cities designed to thrive amid rising seas. “We’re in a process that would be mind-boggling to anybody – we’re trying to foresee of the future,” Kohen says. “It is a duty and a privilege of academia, which is not hinged to politics and economics, to go beyond those influences and generate a vision. Not everyone will be accepting of that vision, but I’ve worked in this long enough to know that in 15 years, these ideas will be common ground for many people.”

What do you want people to understand about adapting to rising seas?

Kohen: Some people think we are sufficiently safe without doing anything.

Clark: Or they think that it’s small fixes or small changes need to be done. Martha and I believe that radical, visionary approaches need to take place.

Kohen: We’ve seen this work in the past with visions for New York, or the Tennessee Valley. There have been moments where a visionary outlook was able to get through. But right now, it looks like we are on an incremental, pixelated way of looking at the way forward, a reactive rather than a stronger, proactive long-range vision.

Clark: Exactly. We need to think 70 years ahead, not five to 10 years.

Kohen: Not raising a road one foot. That’s money not well spent.

Clark: The difficulty is getting the people who are stakeholders to believe in it. But with the increase in storms and flooding in South Florida, even developers are talking about it.

Kohen: The science is there. The knowledge is there. The impulse to get it done is what needs to be built up.

Radical visions:

Kohen: One project we’re working on is called the Sea Belt. What is going to happen with all the coastal towers? Are we going to lose 70 stories of real estate because they get their feet wet? We have strategies and proposals to allow them to complete their life cycle, otherwise losses and abandonment and degradation are going to take place.

Clark: One of the things we try to think about is how to use land development strategies we already know – island development, canal communities — but do it in a smarter way. One of the projects we have for Miami Beach is creating new barrier islands which are well built and high, so they become developable and help protect the bay side of Miami Beach. We also have proposals for canal communities along the Miami River to work with the water in established communities and allow people to remain along the Miami River.

What do you want your students to understand?

Clark: What they dream of and what they imagine in school is possible. Sometimes they think the projects they’re working on in class are not having an impact. We try to get them out meeting stakeholders and working on projects in the community so they can see that cities look to academia for ideas. We’re embracing the idea of a land-grant institution. As much as possible, we try to share our work outside of academia. It’s very important to share what’s possible.

Read about Clark and Kohen’s efforts in Puerto Rico’s recovery from Hurricane Maria in this story from Explore magazine.

Artwork: "From the series: Annual Cycle of the Flooded Rainforest, 2009–2010" by Abel Rodríguez, courtesy of the artist and the Tropenbos International Colombia’s Archive

“The arts are the raw material for imagining the future.”

Associate professor of English

The creator of UF’s Imagining Climate Change initiative breaks down barriers between science and the arts to envision what’s possible.

How can the arts help us improve the world to come?

“Literature and art are tools for thinking about alternate futures. They give you a way of thinking through scenarios and asking, ‘Do I want to live in a world like that?’ If the answer is no, the next question is, ‘What do I do to make sure we don’t get there?’”

You created two classes around “The World to Come.” How did students react to the exhibition?

“I had a number of students who felt they had been compelled to re-examine some of the priorities they had about what they were going to do, what they were going to study, what they aspired to, how they were going to measure their success in life. I don’t want to take very much credit for it, but I felt like the class gave them the opportunity to have that strong response.”

What does the Imagining Climate Change initiative do?

“What we’ve tried to do is to create a dialogue across the physical and biological sciences with the humanities and the arts. As a land-, sea- and space-grant institution, we’ve got tremendous scholars working in all these areas. We just needed to create a venue where those conversations can happen.”

What do you hope will come out of those conversations?

“We are facing what may be the greatest crisis our civilization has faced. Everyone needs to be involved and everyone needs to have a say in it. I want the geologist to talk to the religion professor. I want the musicologist to talk to the chemist. I want these kinds of almost radically impractical conversations to happen, because it’s easy to talk about what we agree on. What’s really productive is where our worlds don’t intersect.”

What do you want students to understand?

“I tell students that cynicism and despair are the refuge of cowards. I want them to be brave enough to help and to find the resolve to act. The world that they see at the end of the 21st century will be dramatically different than the world their parents or grandparents grew up in. They have to find the resources to adapt to that world and try to safeguard what they think is important. If you simply wring your hands about how messed up things are going to be, you’re ensuring they’re going to be messed up.”

Read more about Harpold’s work in these Ytori and Explore magazine stories.

Video by Lyon Duong and Brianne Lehan/UF Photography. Artwork: "Caribou Migration" by Subhankar Banerjee, 2002, loan courtesy of Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire; purchased through the Charles F. Venrick 1936 Fund

What can oncology learn from ecology?

professor of neurosurgery, UF Health

professor of wildlife ecology and conservation, UF/IFAS

Can wisdom from wildlife help us outsmart cancer? That’s what neuroscientist Brent Reynolds and ecologist Madan Oli’s ten-year collaboration asks — and answers. Together, they have launched a discipline called eco-oncology, applying what we know about the ecology of animal populations to tumor cells, which communicate, migrate and reproduce much as wildlife does. One key lesson: When managing a pest that’s plaguing an agricultural crop, it’s rarely beneficial to try to defeat it completely. That approach can leave behind only the hardiest invaders, which then come back even stronger. The same is true for tumors. Instead of pummeling them with chemotherapy until only the strongest tumor cells remain, could we manage the population, keeping the toughest ones in check? Lessons like these, drawn from ecology, could reshape our approach to cancer treatment.

Artwork: "Yanomami" by Claudia Andujar from O Invisivel series, 1976, courtesy of Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo

“The Amazon is essential.”

Professor of Geography and Latin American studies, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and Center for Latin American Studies

For more than 20 years, Walker has journeyed into the Amazon basin, combining remote-sensing data and field interviews of farmers, loggers, ranchers and indigenous groups to reveal urgent threats to the area and its people.

What keeps you motivated?

“I’ve seen the most beautiful places on the planet, places where people have rarely been. I’m drawn back because of that and also because of the compelling problems. The Amazon is under extreme threat right now. I don’t think you can address problems such as tropical deforestation by simply looking at satellite images. The only place you can really understand it is by going face to face with the people.”

What concerns you most?

"Close to 20 percent of the forest is gone — an area larger than Texas up in smoke. Climate models tell you if you lose another 20 percent, the entire forest could disappear, because you fundamentally change the region’s climatology. That’s the tipping point. For me the battleground right now is the Central Amazon basin and the Tapajós River valley — the last right-bank tributary of the Amazon River that hasn’t been dammed. It’s an unbelievably beautiful place and the homeland of the Munduruku people. The battle lines are drawn, and the Munduruku have shown themselves ready to defend what’s theirs. The missing piece now is domestic and global awareness that the Munduruku have a just cause and need to be supported. The question for me really hinges on whether or not that will materialize. If it doesn’t, the Amazon as we know it will cease to exist in ten years."

How will that affect us?

"A disturbance on one part of the global surface can impact a place far, far away. Some computer models show that a desiccated Amazon could actually reduce rainfalls and affect agriculture in the Mississippi Valley. On the less tangible side, the Amazon is the richest store of biodiversity on the planet. You need to have that in order to keep the planet capable of evolutionary adaptation. The Amazon is essential in that respect. And anyone concerned about cultural variety and the integrity of native peoples has to place very high value on the Amazon, because it’s the only place where you really have that amount of cultural richness."

What impact do you hope to have?

"I try to write articles that show what’s going on. If people read them and wake up to the issue, my articles have done what I hoped they would do. In Brazil in particular, I hope my work develops some consciousness and awareness of the infrastructure plans in the works right now that people just don’t know about that are a massive threat to the integrity of Amazonia."

What can people do?

"What I really want is for people to become aware and start protesting again. I wish they would stand up and get angry. They can start petition drives in support of the Munduruku or raise legal funds for them. The citizenry can take this issue to the United Nations. That’s something we could do as global citizens that could lead nation-states to put fiscal pressure on Brazil or even lead to litigation in a world court. That could achieve success, I think."

What gives you hope?

"I have a number of extremely competent graduate students in the Amazon working with indigenous people on these conflicts. I think I’ve imparted to them some motivation to do what they’re doing, and they are definitely advocates. They will continue in the face of great odds. The greater the challenge, the harder they fight."

Read a first-person account of Walker's work in the Amazon in this essay from Ytori magazine.

Artwork: "Swamp and Pipeline, Cancer Alley, Louisiana" by Richard Misrach, 1998, museum purchase, gift of Dr. and Mrs. David A. Cofrin

Artwork: "Swamp and Pipeline, Cancer Alley, Louisiana" by Richard Misrach, 1998, museum purchase, gift of Dr. and Mrs. David A. Cofrin

“We’re not just here to dabble around. We’re here to answer questions.”

Assistant professor, Engineering School of Sustainable Infrastructure & Environment, Wertheim College of Engineering

A college ice hockey player, Angelini turned her penchant for teamwork and tough challenges toward science and has been working on coastal conservation ever since.

How do you describe your work?

"Understanding and restoring resilient coastal ecosystems"

What do you wish people understood?

Coastal wetlands can protect us from storms and algae blooms and support fishing and tourism, but they remain underappreciated, Angelini says. “A marsh is not a wasteland. A marsh is something that brings us tremendous value. Changing that perception and having us cherish these systems rather than abuse them and develop over them is a message I want to get out.”

What keeps you motivated?

“We’re constantly learning new things about how the environment is working, and to me it’s always fascinating. I’ll stay motivated by my own intrigue, but I also feel really compassionate — and passionate — about these systems because of how I’ve seen them degrade over my own time as a scientist, which has only been 10 years. I’m watching them change in front of my eyes.”

How do you stay optimistic?

“I’ve been working a lot more with managers here in Florida that are on the ground doing restoration activities. I almost think it’s the opposite of what’s happening in the political climate of divisions, of folks not talking to each other. There’s increased communication going on between scientists and managers where we’re able to do more science-based management and scientists are doing more research that’s relevant — immediately relevant — to management.”

The importance of getting muddy:

“I want to give my students a love of being in the field observing nature and having that inspire the work they do. It’s so easy to sit at a computer and not be in the mud interacting with the system they’re studying, but being in nature is really valuable for understanding it and getting it right. I never want to get away from those fundamental skills.”

What can we do?

“Every oceanfront owner should be a steward of the coastal dunes in front of their homes. Every person living on the edge of a salt marsh should do what they can to protect those systems. People who have docks can put out features that enhance their ecological value — they could be supporting oysters or enhancing habitat for fish.” For ideas, visit https://www.flseagrant.org/florida-living-shorelines/.

Artwork: "The bird of Hermes is my name, eating my wings to make me tame" by Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla, 2010, courtesy of the artists and Lisson Gallery

Artwork: "The bird of Hermes is my name, eating my wings to make me tame" by Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla, 2010, courtesy of the artists and Lisson Gallery

“Things are changing in our field. It’s an exciting time right now.”

Interdisciplinary doctoral candidate, School of Natural Resources and Environment & Florida Museum of Natural History

When she’s not studying salamanders, this ecologist uses social media to make science more inclusive and accessible and draws on psychology to help science resonate beyond the lab.

Hanging with #HERpers

On the way to a conference on reptiles and amphibians in a van full of female herpetologists, Hecht shared a picture of the group and tagged it #HERpers. What started as a pun became a movement as female herpetologists, both amateur and professional, began using the hashtag to share photos of their adventures. “To be able to brush off the idea that women don’t like these things is huge for me. I’ve seen a couple of tweets from moms with little girls that are into in reptiles and amphibians. People will tell them, ‘You can’t do that, that’s for boys.’ Now they have a whole community of representation.” With the group Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation, she’s branching out to #herpetALLogy to include other underrepresented groups. “It’s leading to some really cool conversations. People are finding each other through it who didn’t know they had other people around like them.”

Why salamanders?

“I could talk about this for the whole day. Salamanders have so many cool adaptations and they’ve been around for so long. They can breathe through their skin. Some can go a really long time without eating. Some of them can regrow their limbs and organs. If you think about all these adaptations that superheroes have, a lot of them could have been inspired by salamanders. There are some that freeze in the permafrost and come out alive. I could go on and on, so I won’t.”

What keeps you motivated?

“What happens to salamanders is not isolated to salamanders. They’re in our water, they’re using our forests. When they are disappearing, that means these habitats and ecosystems are not doing well in general. What’s happening to them is happening to us.”

Scientists as humans

Hecht’s outreach work strives to show scientists as regular people. In a recent storytelling event at the Florida Museum of Natural History, she traced her career through the scars she’s acquired through science mishaps. “Showing the everyday life of scientists is so powerful,” she says. “We make mistakes sometimes. We’re not geniuses who know everything. That’s a huge barrier sometimes keeping out people who might have wonderful ideas, but feel that they are not the right fit for science. I don’t think there is a right fit for science necessarily.”

Artwork: "CF000668, unaltered stomach contents of juvenile Laysan albatross (2009)" by Chris Jordan from the series Midway: Message from the Gyre, 2009, courtesy of the artist

"Little by little, a little makes a lot."

UF/IFAS Extension Florida Sea Grant agent

Up to 95 percent of litter in the ocean is plastic, which harms wildlife and makes its way into our food and water. McGuire has inspired thousands to make small changes to reduce plastic waste.

Describe your work:

“My job is to teach people about the coastal environment and the ways human actions impact it.”

Taking the pledge:

McGuire created the Florida Microplastic Awareness Project, which offers eight ways to cut plastic waste, from using sustainable shopping bags to choosing natural fabrics over synthetics. “I’m often asked, ‘What can one person do?’ One person can do a lot! I’m blown away by the actions people are willing to take.”

Small changes add up:

“If you go to a fast food restaurant once a week and use a reusable cup instead of a disposable cup, lid and straw, that’s more than 150 pieces of plastic a year you’re no longer throwing away. Little by little, a little makes a lot.”

What’s next?

“We ultimately need policy changes, whether it’s climate change, plastics in the ocean, coastal erosion or invasive species. But by raising awareness and providing people with actions they can take, I really do believe that in the long term, people will band together and things will happen at a higher level.”

How about the short term?

“I’d love to get people to rethink the way they shop. You can buy fruits and vegetables loose instead of in a plastic bag or on a foam tray.” McGuire also carries a container in her car for restaurant leftovers and even a mess kit to avoid disposable plates and utensils. For more ideas, visit plasticaware.org.

Portrait by Brianne Lehan and Lyon Duong/UF Photography. Artwork: "NSA-Tapped Fiber Optic Cable Landing Site, Miami Beach, Florida, United States" by Trevor Paglen, 2015, museum purchase, funds provided by The Caroline Julier and James G. Richardson Acquisition Fund and The Fogler Family Endowment

"Change is coming. You can have your head in the sand about it, or you can find ways to address it.”

Director, Levin College of Law Conservation Clinic; statewide legal specialist for Florida Sea Grant

A lifelong love of the outdoors led Ankersen to a career in environmental law, where he and his students work worldwide to protect critical ecosystems and help coastal communities plan ahead.

How do you describe your work?

Innovative conservation solutions through law and experiential learning

Success stories:

Ankersen and his Conservation Clinic students have helped coastal communities in Punta Gorda, Yankeetown, Cedar Key and Hernando County, Florida, prepare for storms and sea-level rise with living shorelines, oyster-reef restoration and adaptation planning and are beginning a similar project in the Florida Keys. They’re helping sea-turtle nesting beaches become more resilient, and they’ve used international law to create avenues to protection for UNESCO World Heritage sites threatened by climate change. Ankersen has also helped launch environmental law clinics at four Latin American universities.

What keeps you motivated?

“Seeing the excitement of young people getting something done in the policy space.”

Embracing the Anthropocene:

The same drive and ingenuity that gave rise to the man-made problems of the Anthropocene could help us solve them, Ankersen says. “Artificial intelligence, de-extinction, novel ecosystems, assisted evolution, geoengineering — all of these things raise ethical questions, but they’re a part of the Anthropocene. It’s worth thinking about that concept more broadly.”

artwork: "White Rhino, Namibia," by Maroesjka Lavigne from the series Land of Nothingness, 2015, courtesy of Robert Mann Gallery, New York

"We will get this right.”

Doctoral candidate, UF/IFAS School of Natural Resources and Environment; Wildlife Ecology and Conservation

A junior scientist with South African National Parks, Nhleko uncovers how stress from poaching affects white rhino populations. What she discovers can help other threatened species.

Rhino mysteries:

“There’s lots of general descriptive information about rhinos — they walk around and nibble on this and that. But we are missing some key elements that will help us save them. We don’t know the nitty gritty,” she said. One key question is how they choose their habitat. It’s not clear why they prefer the southern part of Kruger National Park over some of the other habitats available in the northern parts of the park. “It’s like there is a line they will not cross. Once we understand what they are looking for, then we may be able to move them from high-poaching areas into suitable habitats in safer areas.”

Fear factor:

Figuring out what scares white rhinos could help protect them. “If we know what stresses them, we could manipulate the environment and make it unsuitable in a way that gets them out of danger, because by themselves, they’re not doing it. They’re not scared of people, but they should be.”

Poaching is more than a wildlife problem:

“What are the social issues that are making people want to do these things? It’s not just a conservation problem. It’s a social problem, it’s a political problem. It’s time we all get together and come up with solutions. More than anything, we need to be thinking outside of our own fields.”

How do you stay optimistic?

“It’s the possibility that we might actually figure something out and save the species. It’s been done before. They’ve saved rhinos from less than 100 individuals left. They weren’t dealing with the same rampant poaching and climate change and degradation of habitat, but it has been done before. If we can learn from what was done then, what we know now and the new knowledge we are gathering, we could save other species from extinction.”

artwork: "Adlene Pierre, Savanne Desolée, Gonaïves, Haiti, September 2008; Mushaq Ahmad Wani and Shafeeqa Mushtaq, Jawahar Nagar, Srinagar, Kashmir, India, October 2014; Jeff and Tracy Waters, Staines-upon-Thames, Surrey, UK, February 2014;" by Gideon Mendel from the series Drowning World, courtesy of the artist and Axis Gallery, New York and New Jersey

“We know we’re the problem, so we also know that we can be the solution.”

Associate professor of geology, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences; faculty fellow at the Florida Museum of Natural History’s Thompson Institute for Earth Systems

How many geologists make repeat appearances in Rolling Stone? Drawing on her years as a schoolteacher, this rock-star climate scientist became a go-to explainer of environmental issues — and her research can help predict what happens next.

Climate CSI:

Dutton’s research looks to the ancient past for indications of what to expect as seas rise. But unlike past climate shifts, natural variations can’t explain today’s rapidly warming climate and rising seas. In op-eds, government meetings and countless media interviews, Dutton takes time to explain that greenhouse gases created by human activity are the cause — and while a handful of vocal climate-change deniers debate this, climate scientists do not. “We’re a little bit like a CSI of the Earth. We’re looking for all these clues of what has happened,” she says. “It turns out CO2is like the dumbest criminal in the world. It leaves evidence all over the place. Everywhere we look, we can see the evidence that this is what’s been happening, which makes it easy for us and is why we don’t debate it.”

What motivates you?

“There’s a lot at stake with climate change and sea level rise. It’s going to affect our access to food, water and energy, which are the fundamental things we need to survive. The majority of people across the U.S. understand that global warming is happening, but the minority of them think that it’s going to affect them. There’s a real disconnect. That’s one of the things that motivates me – to help people connect those dots.”

How do you stay optimistic?

“There are actually a lot of positive changes happening. I’m really encouraged by how much is happening at the state level. Wind and solar have now dropped in price enough that the economic argument is straightforward. The technology’s already in place. We just need to decide to use it. And the sooner we make this change, the better the final outcome is.”

What can we do?

“Go out and talk about climate change, because so many people are afraid to even bring up the issue because it’s so polarizing and people can get so upset about it. But if we don’t talk about it, we won’t be able to adapt or to deal with it or to plan or any of those things if we’re too afraid to even talk about the issue. That is something all of us can do that can have a huge impact.” (For reliable climate information, Dutton recommends realclimate.org, skepticalscience.com or the Global Weirding video series.)

Read more about Dutton’s work in this piece from Ytori magazine.

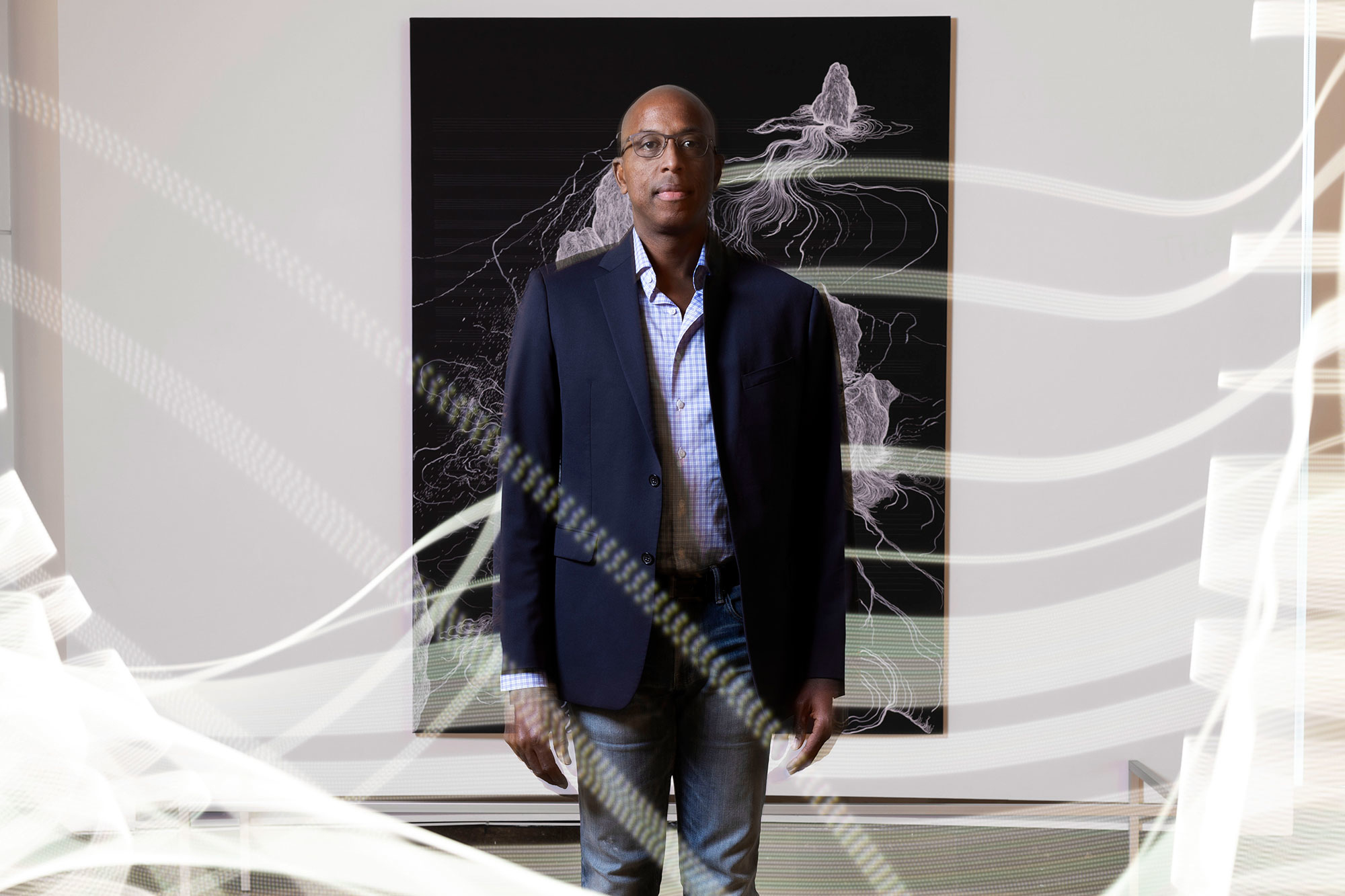

"Ornamental Mountains and Seas—Monster and Cloud" by Haegue Yang, 2011, museum purchase, funds provided by the Caroline Julier and James G. Richardson Acquisition Fund and the David A. Cofrin Fund for Asian Art

"Energy is supposed to make our lives better"

Associate professor of mechanical engineering, Herbert Wertheim College of Engineering

Buildings consume almost half of the energy used in the United States. Barooah works on ways to reduce consumption while delivering better results. Next up: Taking his expertise public to help inform policy.

Describe your work:

Sustainability through intelligent energy use

How can buildings be more energy efficient?

Barooah likens the way buildings use energy to driving a car in third gear all the time: It works, but it’s not efficient. He envisions a future where buildings have the equivalent of an automatic transmission. “We need better algorithms to make these systems shift gear automatically, all the time. I think about how to create software that will make these things run in an intelligent manner, autonomously, without human beings trying to figure out what to do next.”

What keeps you motivated?

“We don’t have a backup planet.”

What do you wish people understood?

LEED certifications are a start, but would you buy a car based on its great gas mileage if there was no way to verify it? “That’s kind of the state of energy efficiency standards, specifically for large buildings. Verification is unsexy, but if you really care about efficiency, energy policy needs to be backed up by measurement.” Barooah points to disclosure standards enacted in New York City and Seattle that can help residents choose efficient buildings, which can incentivize smarter energy use.

How do you stay optimistic?

“As a university professor, I deal with young people, and they don’t come with preconceived notions. I usually find that it’s very difficult to change anybody’s opinion as long as that anybody’s an adult. The younger the person is, they actually come with a fresh mindset. Even if they come with an opinion, they’re far more willing to change their opinion when presented with new facts.”

What’s next?

“I’d like to educate policymakers to make sure they’re asking the right questions. As engineers, we can come up with technologies, but unless the policy framework is there to make sure the right technologies are used, then things are not going to change. How do I inform public policy so that they have all the tools to make the right decisions and not get caught up in buzzwords? It’s on us to make sure that happens.”

artwork: "Spatial Intervention (1)" by Nicole Six & Paul Petritsch, 2002, courtesy of the artists

"Artists can change the status quo."

curator of “The World to Come: Art in the Age of the Anthropocene” at UF’s Harn Museum of Art

Kerry Oliver-Smith looked at the world around her and felt concerned. So she did what curators do: She turned to art to spark conversations that aren’t always possible elsewhere.

In her final exhibition as curator of contemporary art for the University of Florida’s Harn Museum, Oliver-Smith gathered works from 45 international artists to show the beauty of the natural world and the threats to its (and our) well-being. Her intention, however, is not gloom and doom, but inspiration.

“Artists can change the status quo,” she says. “I hope that when people leave here, they feel the urgency and importance of our world and what a miracle it is — and that they will put all their efforts forward to help us keep whole.”

After leaving the Harn March 3, “The World to Come” will travel to the University of Michigan Museum of Art from April 27-July 28, 2019. The exhibition is supported by the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, UF Office of the Provost, National Endowment for the Arts, C. Frederick and Aase B. Thompson Foundation, Ken and Laura Berns, Daniel and Kathleen Hayman, Ken and Linda McGurn, Susan Milbrath, an anonymous foundation, Visit Gainesville, UF Center for Humanities and the Public Sphere, UF Office of Research, Robert and Carolyn Thoburn, UF Biodiversity Institute, UF Center for Latin American Studies, UF Water Institute and UF Department of English “Imagining Climate Change” program with additional support from a group of environmentally- minded supporters, the Robert C. and Nancy Magoon Contemporary Exhibition and Publication Endowment, Harn Program Endowment and the Harn Annual Fund.