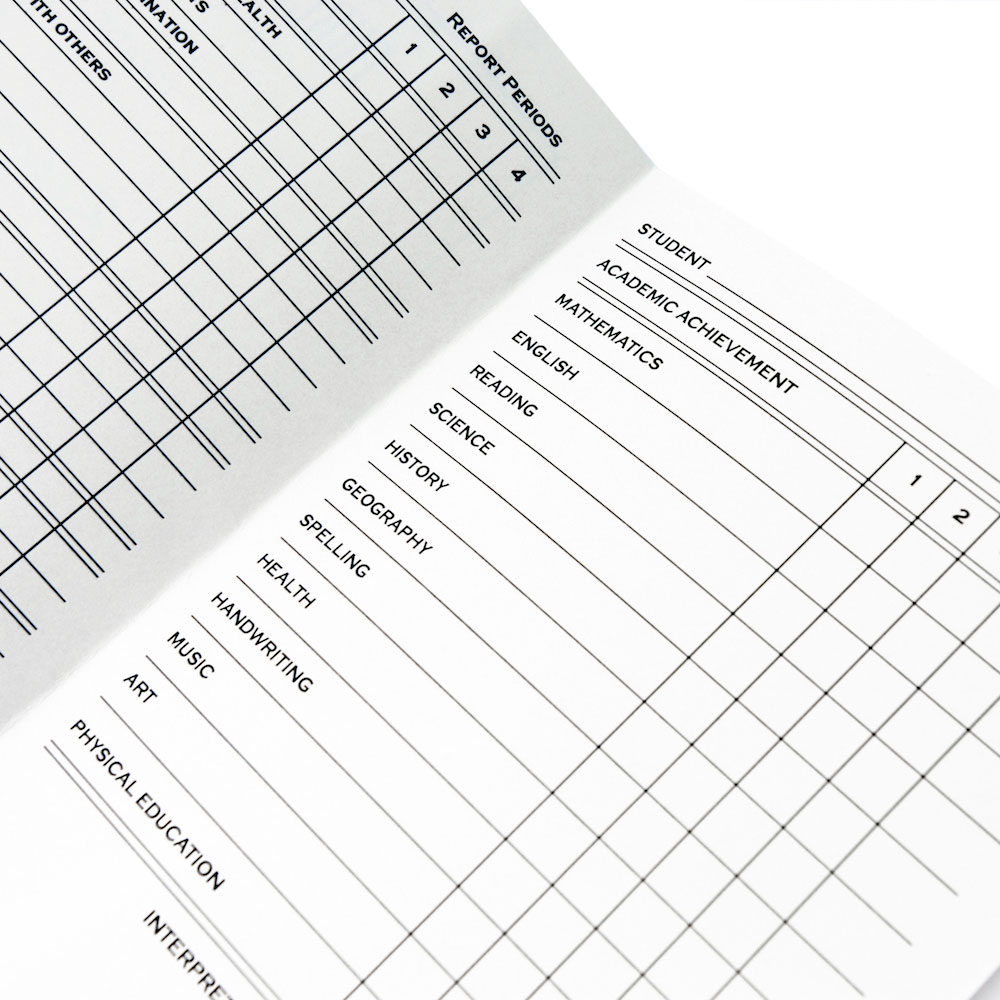

While talking to a pediatrician and fellow early-childhood researcher, Dr. Melissa Bright heard something that stopped her in her tracks: Child abuse spikes after report cards come out.

Bright, a research scientist in the University of Florida’s Anita Zucker Center for Excellence in Early Childhood Studies, couldn’t find any studies to back up what doctors have long observed. So she and the pediatrician, Dr. Randell Alexander, chief of the Division of Child Protection and Forensic Pediatrics at the UF College of Medicine in Jacksonville, collaborated with other scientists to launch one.

After comparing a year’s worth of verified child abuse cases to the dates elementary school report cards were issued, the researchers found a correlation between report cards and child abuse — but only when grades went home on a Friday.

On Saturdays following report card Fridays, cases of child abuse verified by the Florida Department of Children and Families were four times higher than other Saturdays. When report cards were issued earlier in the week, however, there was no increase in abuse cases. The study was published today in the journal JAMA Pediatrics.

“It’s a pretty astonishing finding,” said Bright, who collaborated with Dr. Sarah Lynne of the Family, Youth, and Community Sciences department in UF’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences and Dr. Julia Graber of UF’s Department of Psychology, as well as Dr. Katherine Masyn of Georgia State University and doctoral student Marcus Waldman of Harvard University.

“It’s sad, but the good news is there's a simple intervention — don't give report cards on Friday.”

Bright wants to extend the research by looking at data from beyond Florida. She also wants to pinpoint the underlying causes of the link between report cards and physical abuse. She and her colleagues suspect that the increase is due to children being physically punished for their grades, “but it might be something else we don't know about,” she said.

In addition to distributing report cards earlier in the week, schools could consider including messaging to help prevent corporal punishment that crosses the line into abuse. But that’s a sticky issue in Florida, where some counties still allow corporal punishment in public schools. (Florida’s not alone: 19 states still allow schools to hit students, according to the Gundersen Center for Effective Discipline.)

Bright hopes the findings will encourage school districts to take the simple step of sending grades home earlier in the week and sees the collaboration as an example of how UF’s research can have real-world impacts.

“I have to feel like my research can really make a difference. That's why I like working with pediatricians and teachers. They're hungry for data to make things better, and I’m excited to use my research knowledge to give them those answers.”